Tanker Stories

In this section we portray how it was flying the Tankers - on Exercises and in Action

After the introduction which follows, you can read three fine articles, the first illustrating the technique, planning and execution of a big fighter deployment and the next two vividly relating the cockpit challenges during Operation Black Buck 1 in the Falklands war.

Following these are some stories from the Tanking operations done during the Daily Mail Air Race in 1969.

Introduction - Victor Tanker to Tanker refuelling - the Nuts and Bolts

If you look through 55 Squadron's history, you will know that back in WW1, the Squadron was operating some pretty close formation flying. Check out the photos over Iraq; there too, there wasn't much space between the aircraft. So you could say, that in the tanker role, 55 Squadron was re-honing its basic skills.

The tanker role requires some very exact formation flying - especially when receiving fuel - which the tankers themselves often had to do... Although this was not new and had been practised previously by the Valiant single point tanker, it hadn't been possible behind the Victor K1 two point aircraft because the vortex from the tanker wing would strike a receiving aircraft asymmetrically. On a large aircraft this would cause intense roll and yaw problems. The one Victor pilot (a fFlight Commander at that) who had attempted to “prod” on a Mk 20 wing pod hose (unofficially...) had broken his probe. Our fighter receivers had the same vortex problem but having a shorter wingspan were able to trim out the roll and yaw tendencies.

The introduction of the Victor K1A three point tanker, having a centre hose with its symmetrical aerodynamic position between the vortices, presented the opportunity once more for large aircraft to receive fuel. The visible sector from the Victor streamlined cockpit with its thick structural beams and large “zero-reader” control box on the combing wasn't well suited to formation flying and the receiver pilots had to find a position where they could get a reasonable view when waiting in the echelon position before being cleared astern the tanker.

Although one or two crews on 55Sqn at this time had experienced the Valiant tanker operation it was necessary to carry out a receiver training programme. The first exercises were done in daylight – later ones at night, with the underside of the tanker illuminated by flood lights and the drogue itself somewhat sporadically lit by three wind driven cycle dynamo lights. Black and red aiming marks were applied to the under fuselage and HDU and could be lined up to cross-check the approach line while closing in.

This was practised on a daily basis over the North Sea on a racetrack pattern known as the "Towline".

The training programme was absolved by all captains once they had been checked out on the basic tanking role. Some picked up the technique quicker than others – much to the displeasure of the rear crews of the “others”, who were subjected to considerable accelerations if the pilot over controlled, as maps, pencils and crew sandwiches levitated in the cockpit and fell to the floor under alternating positive and negative G. Don't forget, many Tanker pilots were selected as "steady types" rather than "fighter types" but soon all could do it. The poor Victors suffered during this phase too, and the engineers were very worried about how quickly the structural “life” of the airframes was being used up.

I was lucky enough to be the copilot of an ex-Valiant captain, who learned the receiving role fast and who permitted me to make a few approaches and contacts myself. Since this meant precise close formation flying and the copilots were mostly young “bloods”, they were dying to get a go and I was no exception. It certainly was a help later on in the career.

The Valiant had had a removable Mk16 HDU (hose drum unit) and this had been modified with more modern control gear for the Victor and became the Mk17 HDU. It was fitted as a permanent component, which meant that the aircraft could no longer be used for bombing as the bomb bay doors were removed and two large permanent tanks were installed, which extended to the under skin of the bomb bay area. The HDU had a fuel jettison (dumping) capability to augment that in the Mk20 refuelling pods under the wings.

Once the receiver aircraft had made contact with the drogue and had flown close enough for the hose (hydraulically balanced at the winding drum) to be wound in by a couple meters the fuel valve in the tanker would open and the fuel pressure in the hose increased to 40/50psi. This pressure was felt on the three jacks which until this time had been locking the receptacle to the probe by spring force and it increased the force required to unplug the probe. This was necessary to prevent blow off of the receptacle as fuel flowed under pressure to the receiver. In an emergency it was still possible to disengage the probe by dropping back rapidly which caused the hose drum to brake and the probe to tug out despite the increased locking pressure.

This would cause a fine mist of fuel to escape and envelop the receiver – still preferable to having the hose break, which could cause a mass of fuel under pressure to be released – sufficient in the worst case to flame out an engine on the receiver...

Occasionally a fault could develop in the hose-drum control system preventing the hose winding in. For this case there was a hose release system which would allow an extended hose to be jettisoned from the Victor. This entailed a flight to the Wash bombing range and first required the hose to be extended to its full length – 120 feet. If this could not be achieved then the hose could not be jettisoned and inevitably the first aircraft which could not jettison landed back at Marham with 80 feet or so of hose trailing behind. We went out to the old FIDO (Fog dispersal system...) tanks near the threshold of Runway 24 to watch the landing. The hose hung steady at approach speed – although lower than at refuelling speeds and the drogue landed on the runway after the threshold with no bounce. The hose continued to drag steadily behind the aircraft during the braking roll. This was good to know. Much later it happened to me and we were able to land and to stream the braking chute with no problem. The valve in the drogue had become jammed and leaked some fuel remaining in the hose onto the runway and taxiway surface until a ground engineer belted it with his trusty hammer. Bringing the hose home in this way was found to give better chances of re-use than jettisoning it in the salty waters of the Wash.

The following shot shows a VictorK2 landing at Marham on RW 24 with the centre hose deployed at what must be at or near the full length in June 1982 (FIDO tanks in the background) and it can be seen that the hose hangs straighter and lower than at refuelling speeds.

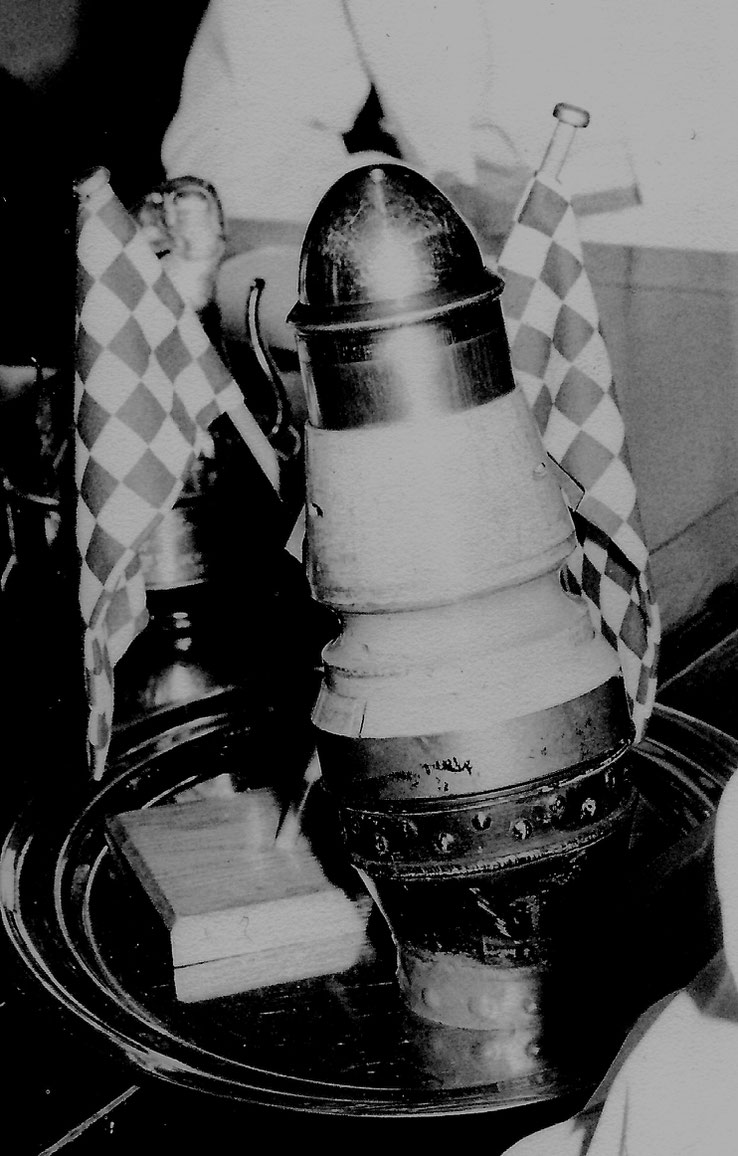

There were other things which could happen, such as a broken probe, which would remain in the basket and be brought back to Marham – in the following shot a probe being returned to its rightful owners at a squadron guest night... The probe had weak rivets deliberately set in one shear-able ring, in order to prevent structural damage to the hose or to the inlet tubing.

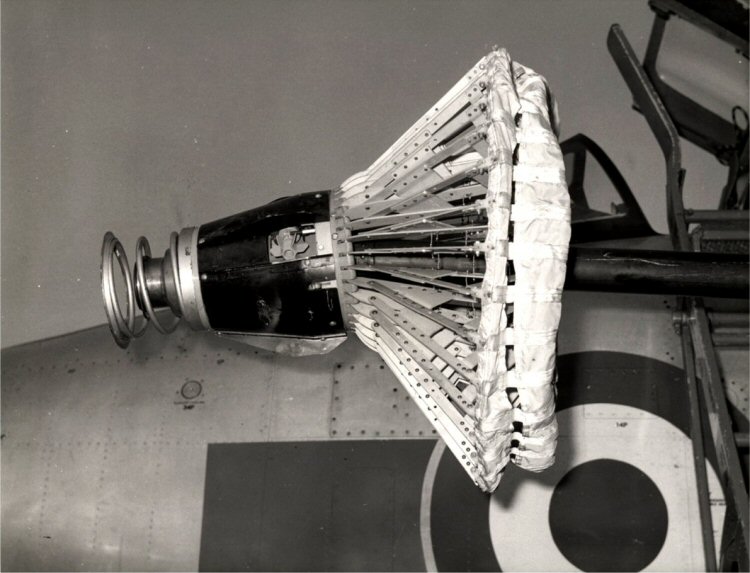

If the receiver pilot were a very rough boy he could cause the drogue to pull off the hose. It shouldn't happen but it did and to prove it, here below is a shot of a Lightning which stole one of our drogues red-handed! This type of incident could cause the “mass of fuel under pressure” flame out alluded to above.

Generally it has to be said, that the Tanking / Receiving operations went very well, though there were some close calls and a tragic refuelling accident, although not in the Tanker / Tanker mode did occur, involving a Victor from another RAF Marham squadron and a Buccaneer, in March 1975. There has since been a memorial erected near Holt in Norfolk, to this loss.

As you can read in John Brown's excellent story of an overseas deployment in this section and the following stories from the Falkland Island raids, a lot of experience and routine as well as skill was required for the whole formation operation to work properly and everyone on the crew was involved in its success.

Here is a diagram of the Mk 17 HDU (Hose Drum Unit) Panel, operated by the Nav Radar

And here is a diagram of the HDU itself

A Tanker as Interceptor?

A Hair raising Encounter by Mike Lawrence

Hi Bill,

The historical photos on the website actually show the picture of the Bear which I intercepted on 14th January 1971. I would like to add some detail to that story...

On the date in question we were due to do a tanker tow line with 11 Sqn but the weather was appalling. All RAF stations were below Red conditions (Red being the lowest useable weather, 800m vis and 200ft ceiling, ed.) except Marham (Victor Tanker base) & Leuchars (Lightning fighter base) - which were just Red.

We sat in the cockpit waiting for Leuchars to stand down, hoping to outlast them in one-upmanship. Finally ATC announced Leuchars was below minimum and we cheered and congratulated ourselves on the win...

But then a voice came on frequency from the Strike controller with the order to scramble - with a code word. The navigators informed me that they had verified the code word from their war bag. We managed to stay on the taxiway through thick fog following the centre line green lights and by some miracle also stayed on the runway while doing an instrument take off. Better to be lucky than skillful eh? As the undercarriage came up ATC declared Marham weather deteriorated below Red.

Anyway after climb, the Strike Controller vectored me onto the Bear. The guns at the rear of the Bear followed us instantly in line astern position. I understand that they were radar guided and locked on…

I was then ordered to destroy the aircraft if it maintained heading, when 3 miles from the coast. (basically bailing out the crew and ramming the Bear)

I tried nudging it around by flying in close echelon starboard and just before 3 miles it turned around. (I might have accidentally jettisoned some fuel over it)

Their co-plot actually waved a red glove (could have been a flag) at me as they turned. I was relieved that I didn't have to ram it...

Somewhere in these proceedings a couple of Lightnings showed up and took the photo (and the credit). I'll forward the letter that was forwarded via Station Commander John Smith to me from Strike command and a copy of the cartoon which accompanied it. (both below, ed.) The message said that requests to arm the Victor K1 would not be approved.

Oh Happy days

Kind regards

Michael Lawrence

A very big Deployment - Operation Hydraulic, 1967 - Related and Illustrated by John Brown

We present this story of an overseas deployment with grateful thanks to John Brown, who originally wrote this story on his blog site in five episodes.Here he describes just about all the technical and operational facets of the tanking "trade" with humour and accuracy.

Operation Hydraulic was the codename for an operation to deploy 13 Lightning Mk6 aircraft of No 74 Squadron from their base at Leuchars, Fife, to RAF Tengah in Singapore. The 14th aircraft, a 2-seater, was sent by sea. No 74 had been the first RAF front line Squadron to operate the Lightning, the RAF's first supersonic fighter, and in 1966 had been re-equipped with the F6 version which could be fitted with additional over wing fuel tanks to extend its unrefuelled range. Nevertheless, for the deployment to Singapore, air-to-air refuelling would be necessary, particularly on the long oceanic transits.

The deployment was scheduled for June 1967. At the time, the RAF's air-to-air refuelling assets comprised 3 squadrons (55, 57 and 214) of converted Handley Page Victor B Mk1 and BMk 1A bombers. The tanker variant was designated BK Mk 1/1A. Several of the conversions had 3 refuelling points: one on each wing for fighter type aircraft, and one on the centre-line (at the rear of the the old bomb bay) which could be used to refuel large receivers, particularly other tankers). However, at the time, few of the Victor crews were qualified to receive fuel from another Victor.

The refuelling task was both complex and potentially complicated. The Lightning was incapable of independent navigation over long distances and therefore must be accompanied by at least one tanker for the entire way. Each Lightning must always have sufficient fuel on board to make an emergency diversion to an alternative airfield in the event of a technical malfunction or failure to receive the required amount of fuel from the tanker. I cannot remember the exact construct but the deployment was arranged in "waves" with a number of Victor Tankers escorting 2 or 4 Lightnings over each leg. There were 4 legs: Marham/Lechars to Akrotiri (Cyprus), Akrotiri to Masirah (Oman), Masirah to Gan (an atoll in the Indian Ocean), and Gan to Tengah Singapore (Butterworth in Penang for the Victors).

And so it was on 4 June 1967, Victor K1A XH588, Captain Flt Lt Eddie Smeeth, Co-Pilot Fg Off John Brown, Navigator Plotter Flt Lt Dennis Maunders, Navigator Radar Flt Lt Bill Bowen, Air Electronics Officer Flt Lt Rick West, and a flying engineer, trussed on the 6th cokpit seat, set off on Wave 1 of the first stage of the deployment to Akrotiri. Several challenges lay ahead: firstly, all the Victors which had taken-off independently had to find each other at height and become a single formation, secondly, the formation of Victors had to rendezvous with the formation of Lightnings which had left Leuchars earlier. Finally, the whole formation of Victors and Lightnings had to set course cross France, refuelling as we went and overcoming the diplomatic hurdles and restrictions that our French and Italian friends had put in the way.

This is what it looked like on climb out from Marham on 4 June:

And this is how it looked as the tankers joined up:

As far as I can remember, we all reached Akrotiri without major alarm and here we all are, apart from the photographer, after landing. Note the empty demijohn of Cyprus Sherry in the forground. Although the intention would have been to replenish it, I think this also shows an early example of environmentally responsible re-cycling.

The whole Gan operation was supported by hundreds of locally employed civilians who sailed to and from the airfield daily from outlying parts of the atoll.

There were no women on the permanent staff and those in transit, on the scheduled VC10, were much admired by the locals who usually found something they needed to be doing in the area reserved for transit passengers whenever the schedule passed through. We passed the time, blissfully, on the beach, swimming, and diving. Some of our number made the boat trip to Hithadoo, about 10 o’clock on the circumference of the atoll, some receiving severe sunburn injuries for their trouble. When we retreated from the sun it was to the bar where alcoholic beverages were, again, incredibly cheap. Indeed, a measure of gin was free; the upturned gin bottle and optic was covered with black tape so that the contents of the bottle were invisible – the person who bought the last shot paid for the whole bottle. Whilst alcohol was cheap, the NAAFI monopoly ensured that staples such as Roses Lime Juice were expensive.

With many thanks to John Brown

Operation Black Buck

The famous Falklands raid on Port Stanley airfield, 1.May 1982.

Here is the report which Martin Todd contributed to the RAF News following his participation in Operation Corporate, which included the Black Buck raids described below. It is also very candid and much appreciated.

Here are two reports by crews directly involved in the raid.

The first is by Victor Captain, Dick Russell, who flew on the attacking Vulcan in the RHS as Receiver expert.

The second is by Bob Tuxford, who captained the Victor tanker which accompanied the Vulcan for the longest distance

Bob and Dick don't mention sweaty hands but reading their reports and seeing the video "Falklands' most Daring Raid" which follows, I can well imagine that they, along with a few others had

them...

We appreciate the "horses' mouth" reports, thank Dick and Bob very much for providing them and can only comment "Good Show"

Operation Black Buck 1 - night 30th April / 1st May 1982

the Vulcan perspective

This is all well documented in the book Vulcan 607.

Briefly, I returned from my tour in Germany in 1981, got current on the Victor 2 again as a QFI but not as an AARI. (AIr to Air Refueling Instructors trained Victor Crews in the receiver role, Ed)

In 1982 the probability of a Falklands conflict was on the horizon and the re training of Victor pilots back to air to air refuelling started in earnest . One sortie got me current both Day and Night - and the next day a Canberra took me to Waddington to help train three Vulcan crews. On arrival I found that I would be with Martin Withers.

Over the next 10 days or so Martin and the two other crews converted to Air to Air Refuelling .

The three of us AARIs came back to Marham to be told that we were now part of the Vulcan crews for whatever might happen, so it was back to Waddington again...

On April the 29th Martin and I with his crew and with the Copilot on the 6th seat flew to Ascension Island in company with another Vulcan, taking on fuel off the coast of Spain. That night, since it was my 50th birthday on the 30th, we celebrated as it turned midnight with a beer or two...

Next morning, rising late we were told to attend a briefing about 1300 for what turned out to be Black Buck 1.

Nice birthday pressie!! On arrival we found the dozen or so Victor crews had already been planning for some hours...

So picking up with the buzz we try to fathom out what part we will play. Our crew is to fly the reserve Vulcan.

Planning complete, some 12 Victors and 2 Vulcans took off at night, I was in the copilot's seat - with Peter Taylor, the usual Copilot - on the 6th seat ( he and l would change seats for the bombing run should we be required, some 6 hours later).

In the climb, the primary Vulcan went unserviceable, so now we are the only Vulcan with a 21000 lb bomb load and going to Port Stanley...

Finding our tanker so far ahead at night in radio silence proved very difficult, but was achieved with the breaking of the silence and asking for a Very cartridge (signal flare, Ed) to be fired from our tanker.

And finding our way from tanker to tanker for our refuelling brackets proved nerve racking to say the least, not helped by two large electrical storms in which one tanker broke his probe and the last tanker - which would now be giving us our fuel performing heroics within the storm changing roles with the Victor that had broken his probe.

All through the last 5 hours or so the Vulcan had been using fuel much faster than planned - so both the final outbound Victor and our Vulcan were short.

The Victor gave us a transfer which left him with insufficient fuel to get back, and we were some 8000 lbs short, so that if our recovery tanker should not make the RV off the coast of Brazil on our return leg, we would have insufficient fuel to make landfall in Brazil.

Peter and I changed seats for the bombing task - which has been well reported elsewhere - and using up our precious fuel at a high rate.

The bombing run completed, we turned and climbed to cruise level, I went back to the Copilot's seat, Martin went to the 6th seat and Peter went to Martin's seat. This was the situation for the next 3 hours or so.

An hour prior to the RV off the coast of Brazi,l Martin got back up front again. Within minutes we started to hear a Nimrod calling us saying that he had us on his radar and some thirty minutes later we heard our recovery tanker, asking us to transmit; this was the start of a tanker - tanker type RV, the sort that we practised back home. Nothing was seen even though we were close until suddenly our tanker rolled out about a mile ahead with his hose trailed. By this time we had rather less fuel then necessary to make the coast of Brazil some 400 miles to the west.

Martin closed up and made a good approach,he plugged in but immediately, as the fuel started to flow it leaked out in a fine spray, partially obscuring the tanker and hose. Having had this problem during the training phase I knew if we broke contact it would be about 20 minutes before the screen cleared sufficiently to make another approach and all this time we were heading away from land. I took control,and with a little commentary from Bob Wright who had come up the ladder to watch I managed to stay in contact and take on about 30000 lbs. Once refuelling was completed we broke contact, moved out to starboard for the 3 1/2 hour transit back to Ascension.

Luck was both with the final outbound Victor and with us - with Ascension scrambling yet another Victor for the returning tanker and the friendly Nimrod tracking us and our final tanker for

the RV off the coast of Brazil... Everyone made it home.

During the transit home we heard on our short wave radio on BBC World service that "a Vulcan had bombed Port Stanley airfield..."

With many thanks to Dick Russell for this report

Operation Black Buck 1 - night 30th April / 1st May 1982

the Victor tanker perspective

I was posted onto 55 Sqn on 1st April 1982. Having flown the Victor K2 tanker for the previous 18 months as pilot Leader on 57 Sqn, my transition to Flight Commander was a baptism of fire. Over the next couple of weeks, I would be tasked to fly the aircraft in a new low-level role, sporting F95 cameras in a nose rig in the former bomb aimer’s compartment, to give us a photo-reconnaissance (PR) capability. Also, a number of ex-27 Sqn Nav Radars appeared during that fortnight to be integrated into the selected three crews to convert us to the role of maritime radar reconnaissance (MRR). Preparations at RAF Marham, the home of the tanker force, were frenetic to say the least. By the 18th April, the first of five crews were deployed to the South Atlantic at the start of a new chapter in the history of air-to-air refuelling (AAR).

As the door was opened for the first time in over nine hours, the cockpit filled with a searing heat from the sun-baked tarmac below. With aching joints, I negotiated the crew ladder to extricate myself from the cramped confines of the Victor’s cabin. As we savoured a cold beer, we were in awe of the forbidding landscape that was littered with barren volcanoes, dotted around our new forward operating base of Wideawake Auxiliary Airfield, Ascension Island (ASI).

Over the next 24 hours, the five tanker crews mucked in with the incumbent RAF detachment personnel and erected the tents that were to form the operations complex. During the afternoon, the second wave of Victor tankers arrived in sequence from RAF Marham. This brought the number of K2s to a total of nine, just less than half of the UK’s Tanker Force. On 20 April 1982, less than 48 hours after my own arrival, the first formation of tankers launched into the South Atlantic sky. The mission was intended as an intelligence gathering opportunity using our newly acquired MRR skills. Two more similar operations were launched at 48-hr intervals to gather much-needed intelligence for the advanced Task Force intent on regaining the South Georgia Islands. From an AAR point of view, the three MRR missions created the opportunity to develop the blueprint for all future air operations conducted from ASI.

On the night of 30 April 1982, No. 1 Group’s tanker crews assembled for the first time along side two Vulcan crews for Operation Black Buck 1. The aim: to bomb the runway at the Argentinian-occupied airfield of Port Stanley on East Falkland Island. The side walls of the briefing tent flapped vigorously as solitary light bulbs hanging from flexes danced in the balmy night breeze. As the sheer enormity of the task unfolded, the complicated refuelling plan was extraordinary even by the standards of the seasoned tanker crews. At this stage, there were no less than thirteen Victor tankers on the ramp at ASI, and all serviceable aircraft would be needed to provide the in-flight refuelling support for a single Vulcan bomber. Eleven K2s in three sections, Red, White, and Blue would be needed to provide the fuel through successive cascading refuelling brackets in order to get the bomber to the cast-off point around 400 nm north of the Falklands. A further seven tankers would plan to launch around 6 hours after the initial outbound wave take-offs to provide two hoses at the so-called Rio Rendezvous, to recover the returning Vulcan to Ascension Island.

Two hours later, the night air was awash with the deafening noise of Conway and Olympus engines. Within minutes, one of the Victors suffered an engine winding down, necessitating one of the ground reserve aircraft to fall in line and take its place in the start sequence. At 45-second intervals, the heavily laden 4-jets took to the runway and laboriously staggered into the air. The carefully-choreographed plan quickly gave way to disarray as the lead tanker in Red section discovered their centreline hose could not be trailed. As if to deliberately test our Ops Controller’s flexibility, the primary Vulcan, ‘Blue 2’, reluctantly announced his intention to abort as the aircraft failed to pressurise during the climb. Undaunted by these early set-backs, Flt Lt Steve ‘Biggles’ Biglands eased across from Blue Section to replace the unserviceable formation leader as ‘White 4’. Flt Lt Martin Withers in the airborne reserve bomber half-heartedly took on the mantle of Primary Vulcan, as the prospect of his early return to the bar was scuppered.

At Bracket 1 after two hours in formation, the four tankers in Red and White Sections paired up and mutually transferred their fuel whilst the remaining tanker in Blue Section refuelled the replacement ‘Blue 2’. Adding to the difficulty of refuelling and formation changes at night, all procedures were undertaken in radio silence to protect the anonymity of the formation. Little did I know therefore that a fuel crisis of significant proportion was rapidly developing as the four aircraft which had offloaded their fuel at Bracket 1 returned to base desperately short of fuel. I was to find out later that each aircraft had to land in turn and ‘stack’ at the end of the single runway as there was insufficient time to backtrack the length of the runway to clear it for the following aircraft. The potential for a motorway pile-up of momentous proportion was narrowly avoided. However, it became obvious to the operations staff at that point that there were some shortcomings in the ambitious fuel plan!

After carefully sequenced refuellings at Bracket 2 around four hours after take-off, the remaining four tankers of Red and White Sections shared their fuel, and the Vulcan was topped up once more. After the refuellings, Allan Skelton as ‘Red 4’ turned for home. Before long, his crew faced another disturbing development as their aircraft was found to be losing fuel through a significant fuel leak. Unaware of this latest crisis, as ‘White 2’, I assumed the role of formation leader for the first time that night and my Plotter John Keeble took over the navigation. Along with Steve Biglands as ‘White 4’ on my wing, and Martin Withers as ‘Blue 2’ in tow, we continued, obliviously, southbound towards the third refuelling bracket.

Around 40 Degrees South, the proverbial hit the fan. Weather activity in the form of towering cumulus clouds enveloped the remaining three aircraft, unseen by us as our radars remained switched off. The pitch-black sky was temporarily illuminated with blinding flashes of lightning, and eerily, St Elmo’s Fire danced erratically around my cockpit windows. According to ‘Sod’s Law’, the turbulence was at its most active just as Biggles lined up astern my centre hose to take his fuel. As the basket flailed wildly on the end of the 80-foot hose, the receiver aircraft repeatably tried to make contact. Biggles finally achieved a good contact and, mercifully, fuel started to flow. However, half way through the scheduled offload, my Nav Radar, Ernie Wallis could see through the periscope that the aircraft behind had become unstable. As waves developed along the length of the hose, the dynamic loads caused the receiver’s probe tip to separate at the design weak-link. Disaster loomed as no further fuel could be transferred to that stricken aircraft. In a desperate attempt to keep the show on the road, I broke radio silence and suggested to Biggles we change places to allow me to take the fuel back. With considerable difficulty, I moved astern Biggles’ rapidly trailed hose and mentally prepared myself to take on fuel, unexpectedly, for the third time that night. Glyn Rees, my CoPilot, hastily set about preparing the fuel tray to configure the tanks to accept the unscheduled fuel uplift. Conditions at this point had not improved. Both tankers must have looked like bucking broncos to the Vulcan pilots desperately trying to maintain visual contact in echelon starboard. After a number of missed approaches, I was aware my flying was getting somewhat erratic, and I was feeling the tiring effects of six hours of close formation flying and two previous maximum onloads of fuel. I made a deliberate attempt to calm down my control inputs and was rewarded finally to establish a latched contact. With just a few thousand pounds of Avtur received, I then had no option but to drop back and separate due to what were still impossible if not dangerous conditions. Miraculously, just at that moment, the clouds dissipated, the turbulence subsided, and the star-lit sky offered up a distinct horizon once more. I was able to make one final contact with relative ease and resume the fuel uplift.

I was well-aware of the fact that Steve Biglands would not be able to take on any more fuel on his return to the Island because of his damaged probe. Accordingly, I broke radio silence briefly to convey to Biggles that he must keep a suitable reserve of fuel for his return transit. A short while afterwards, I was offered the flashing lights on the HDU to indicate that I had been given all the fuel that he had to offer. I dropped back and cleared my leader to turn left immediately to return to base. There was time finally to take a moment and reflect on the somewhat chaotic activity of the last half hour. It quickly became apparent that we were well short of the fuel on board that was detailed in the fuel plan. However, of greater concern to me, was the potential damage to my basket encountered during Biggles’ broken probe incident. Before any consideration could be given to the onward plan, if my hose and basket combination had been compromised, I might not have been able to transfer any further fuel to the Vulcan. Accordingly, I cleared Withers astern to assess the serviceability of my refuelling equipment. Unable to decide unequivocally whether or not the basket was serviceable, there was no option but to suggest a contact. In clear weather conditions, the Vulcan had no problem making what looked like a normally latched contact. To make certain, we then passed a nominal 5,000lbs in a test transfer to prove the respective refuelling systems. With that hurdle overcome, we pressed on towards the rapidly approaching final refuelling bracket.

At this stage of the mission, I was forced to take stock of the predicament in which we found ourselves. On the one hand, it was conceivable that I could have turned the formation back towards our safe haven of Ascension Island while sufficient fuel remained in the formation. However, after so many crews had pushed themselves to the limit to get us to that point, I was predisposed to completing the task, despite the dwindling fuel reserves. However, I could only press on with the approval and support of my crew. On asking them individually for their views, to a man, they cited that as we had got that far, we might as well finish the job! Without further discussion, we set about deciding what fuel we could spare to give the Vulcan at Bracket 4, whilst keeping a sufficient amount to get close enough to Ascension Island to seek out a Terminal Airborne Tanker. Although this had not been specified as a possibility because of the limited number of airframes, I did have confidence that the Air Head Commander on the island, Gp Capt Jeremy Price and his Ops Staff would be looking out for our interests. Woefully shy of the planned fuel on board by this stage, we nevertheless gave the bomber a final fuel transfer, and after some reluctance to leave us, Martin Withers turned his Vulcan towards the target, and the rest as they say is history.

Needless to say, the next four hours were a mixture of thoughtful reflection and anticipated expectations. Barely an hour after we had despatched the bomber, my AEO Mike Beer excitedly announced over the crew intercom “SUPERFUSE”. This was the codeword for the successful completion of the bombing run against Port Stanley. I can say there was a moment of pure euphoria in the cockpit while we punched the air with our fists and metaphorically patted each other on the back at what we felt we had helped to achieve. Furthermore, my faith in the Tanker Force was fully justified when, three hours later, that famous crescent wing eased into view over a cloudless South Atlantic sky. Captained by OC 55 Sqn, Wg Cdr Colin Seymour had been despatched towards us after operations had received confirmation of our predicament. Still 3 hours flying time from Wideawake Airfield, XL189’s fuel gauges showed barely one hour’s fuel left in our tanks! The success of that final contact could have potentially jeopardized any follow-up operations mounted by the RAF from Ascension Island in support of the South Atlantic Task Force. However, despite the pressure of that final prod, I was not going to take any chances. My first approach missed, and the probe gently slid by the basket at the 3 o’clock position – in what I like to think of my best ever missed contact. I was absolutely calm as I gently eased the aircraft back to the pre-contact position for a second approach. As my probe tip entered the basket, it barely touched the spokes as the tip nestled centrally inside the reception coupling and a satisfying ‘clunk’ was heard. After pushing in a few feet of hose, the green lights illuminated indicating that fuel was flowing into the tanks. Once sufficient fuel had been onloaded, the remaining flight was uneventful to a final landing on Ascension after some 14 hours and 5 minutes in the air.

Thanks a lot Bob Tuxford for this report

Here is Bob's crew after landing: Ernie Wallis, Mike Beer, Bob Tuxford, Glyn Rees and John Keeble - apparently holding spare cans of engine oil...

And here is the Black Buck story as shown on Channel 4 Television

How it was planned

This detailed plan courtesy of Bob Tuxford

With permission of the artist, Ronald Wong, his dramatic painting of the events during the storm, titled "40° South".

There is more on the Falkland Campaign in the Typewritten Squadron History, Ch 14

Danny's Castle - Ascension Island...

The story behind Danny's Castle - Ascension; in the early days at the flight line the only "facilities" were three or four thunderboxes screened by four foot high hessian, giving little privacy. (Obviously with the temperature at 30 degrees plus, they were situated some distance downwind from the work area.)

So, with some ingenuity and 'acquisition' of materials the airframe trade chief, Danny, built this castle affording more privacy and some protection from the elements. Initially known as Danny's Castle but more latterly as Racasan Towers, it was a welcome sight for those crews returning from the long slot who couldn't make it to the other side of the airfield!

Thanks to Brian Martin

The Daily Mail Trans-Atlantic Air Race 1969

In 2019, it has been 50 years since the Daily Mail Air Race between London and New York in both directions. The event, for the Vickers Trophy was itself to commemorate the historic first non-stop North Atlantic flight of Alcock and Brown in the Vickers Vimy in June 1919. The tops of the GPO Tower in London and the Empire State Building in New York were designated start and finish points! All sorts of people took part, in all sorts of ways and it wasn't long before the Tanker Force was roped in for a couple of projects, one refuelling Harriers Westbound and one refueling Phantoms Eastbound. Being the Tanker Force, we had to be on a winner - and 55 Squadron was, with its three Royal Navy Phantoms as customers getting the fastest overall prize. There was an event to mark the occasion on 8. May 2019 at Brooklands Museum. Some pictures of the event and recollections are included below!

Some photos of the event held at Brooklands Museum 50 years later - also attended by our dutiful members...

With thanks to Colin Griffiths